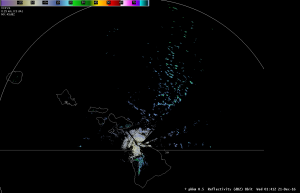

Reflectivity image from the Kohala radar showing trade wind showers much farther away than it should. (Animated radar loop)

Yesterday afternoon something strange showed up on the Kohala radar–a bunch of trade wind showers north of the Big Island. Showers were to be expected, as we were watching an area of open-cell cumulus clouds approach from the east. The strange part is that they extended to the extreme edge of the radar range, about 285 miles away. At that point, the radar beam could be sampling up to 50,000 feet, quite a bit higher than these showers. What gives? Since we weren’t looking at cumulonimbus clouds on satellite, we were looking at a nice example of radar beam ducting.

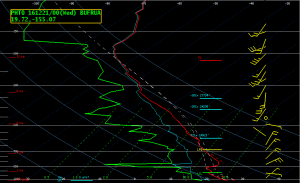

NWS radars look at multiple levels of the atmosphere, but the scans aren’t parallel to the ground. The lowest view is 0.5° above the horizon, which means that the beam still gets higher in altitude the farther it travels. (The radar beam also expands in size, which means it samples a larger portion of the atmosphere as well.) In normal conditions, at the edge of its range the radar should be sampling somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000 feet. (For additional background information, there are articles I wrote on weather radar basics and non-meteorological radar returns [including ducting] for the General Aviation Council of Hawaii newsletter.)

Trade winds were building back across the state after being absent for a while, and there was a stable, low inversion around 5,000 feet. The inversion had strengthened since the 2 am sounding, and the lower atmosphere below the inversion had also dried out quite a bit. In many instances of ducting, the inversion will be very low (such as surface-based at night), and the beam will be directed back into the ground, creating a large area of ground clutter. In this case, the radar beam was ducted along the inversion so that it sampled the showery cumulus field for a couple hundred miles longer than it should have.

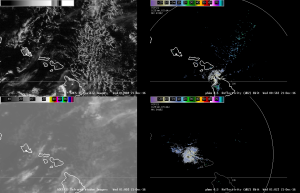

The four-panel image to the right shows comparison of multiple radar and satellite images. The upper right shows the 0.5° reflectivity from the Kohala radar and the lower right shows the 0.5° reflectivity from the Molokai radar. (Note that the Molokai radar wasn’t experiencing the same beam ducting problem.) The upper left shows the visible satellite image and the lower left shows the infrared satellite image. (Note that the cloud tops in infrared are still quite warm, while based on the radar beam height and the Hilo sounding they should be colder than -40°C.) Click on the image for a larger static image or view a five hour loop.)

The four-panel image to the right shows comparison of multiple radar and satellite images. The upper right shows the 0.5° reflectivity from the Kohala radar and the lower right shows the 0.5° reflectivity from the Molokai radar. (Note that the Molokai radar wasn’t experiencing the same beam ducting problem.) The upper left shows the visible satellite image and the lower left shows the infrared satellite image. (Note that the cloud tops in infrared are still quite warm, while based on the radar beam height and the Hilo sounding they should be colder than -40°C.) Click on the image for a larger static image or view a five hour loop.)