There has been a surprising amount of interest in Central Pacific tropical cyclone names recently, due entirely to Hurricane Walaka.

Category Archives: Weather

Walaka: Camera 1, Camera 2

Hurricane Walaka is located just east of 170°W. It’s still located closer to NOAA’s old GOES-West satellite than to JMA’s Himawari, but the newer satellite has the better resolution to make up for the distance.

Reaching the End of the List

Tropical cyclones that form in the Central Pacific are named using four rotating lists of Hawaiian names. We may soon use the last name from the fourth list. What makes that notable is that it has never happened before.

Other Sources of Weather Information

One of the reasons I like staffing a NOAA/National Weather Service booth at aviation-related events (such as the recent Hawaii Aviation Day at the Hawaii State Capitol) is because of the questions that pilots ask. If one person asks a question, chances are there are others out there wondering the same thing. This article will highlight a few sources of weather information available on the NWS Honolulu website that may be useful but not well known, and also introduce an initiative that’s designed to improve communication between our office and community groups interested in improving weather safety and preparedness.

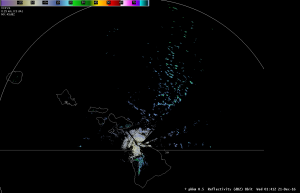

Example of Radar Beam Ducting

Reflectivity image from the Kohala radar showing trade wind showers much farther away than it should. (Animated radar loop)

Yesterday afternoon something strange showed up on the Kohala radar–a bunch of trade wind showers north of the Big Island. Showers were to be expected, as we were watching an area of open-cell cumulus clouds approach from the east. The strange part is that they extended to the extreme edge of the radar range, about 285 miles away. At that point, the radar beam could be sampling up to 50,000 feet, quite a bit higher than these showers. What gives? Since we weren’t looking at cumulonimbus clouds on satellite, we were looking at a nice example of radar beam ducting.

Winds Aloft: Sources of Information

The Summer 2016 newsletter article on trade wind inversions referenced the weather balloons we launch twice a day from Lihue and Hilo, which measure winds aloft in addition to temperature and moisture. In this article we’ll look at two additional sources of wind information: radar wind observations and the automated winds aloft forecasts.

Trade Wind Inversions

In the Winter 2014 newsletter, I talked about trade winds and briefly touched on trade wind inversions. Inversions have a big impact on the weather we see in Hawaii, and knowing more about them may be of interest to pilots.

What Is An Inversion?

Temperature normally decreases with height in the atmosphere. (The higher you go, the colder it gets.) For dry air, the temperature drops about 5.4°F for every 1000 feet, or about 9.8°C for every kilometer. An inversion is a layer where the temperature either remains the same or increases with height. It is the result of an outside force, such as a change in airmass along a front where warm air overruns cold air. The typical driving force we see in Hawaii associated with the trade winds is due to sinking air associated with high pressure systems.

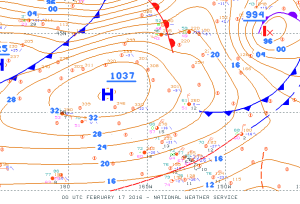

Low Level Wind Shear

On February 16th, 2016, a 1037mb high northwest of the state brought strong and gusty northeast trade winds to the islands. We received many reports of low-level wind shear, some which we were due to non-convective wind shear and some of which were due to convective mixing and gusty winds. What are the different types of wind shear, when is wind shear included in a TAF, and what can you do to mitigate the risk from it when you fly?

When Weather Radar Measures More Than Weather

Note: I originally wrote this article for the General Aviation Council of Hawaii Spring 2015 newsletter. Hopefully you will find it interesting and educational as well. –JB

(For more background on weather radar basics and an overview of the different radars in Hawaii, see the GACH newsletter from Fall 2012.)

Not everything you see on a weather radar image is necessarily a weather feature. Weather radars use a series of complex algorithms to filter out energy from non-meteorological returns. In general terms, if an object is stationary, then it’s most likely not weather-related. For example, a mountain will reflect a lot of energy back to the radar. Luckily, mountains don’t move (much), and the radar will identify and filter out these types of returns. However, no algorithm is perfect, and some returns make it into the final reflectivity product even though they’re not actually precipitation. Here are a few of the more common non-meteorological returns we see in Hawaii:

El Niño and Hawaii Weather

Note: I originally wrote this article for the General Aviation Council of Hawaii Spring 2014 newsletter. While this seasonal outlook was from last spring, the typical impacts during El Niño remain consistent. Hopefully you will still find it interesting and useful. –JB

The spring 2014 forecast [view the latest forecast] from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center indicates that there is a greater than 50 percent chance that El Niño conditions will develop during the summer of 2014, and continue into the winter of 2014-2015. What is El Niño and what does it mean for weather in Hawaii?