Note: I originally wrote this article for the General Aviation Council of Hawaii Winter 2014 newsletter, hence the aviation focus. Hopefully you will find it interesting and educational as well. –JB

In the last article we discussed severe weather features such as tornadoes and water spouts. These weather phenomena are not common, especially in Hawaii. For the bulk of the year our weather is driven by the trade winds. In this article we’ll take a look at what drives the trades, how they affect our weather, and the types of impacts to aviation that we may see from them.

Background

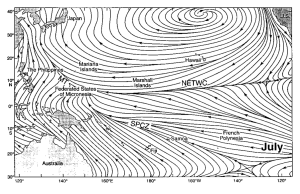

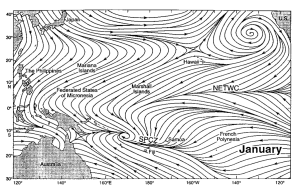

Trade winds originate from high pressure located in the subtropics, generally between 30 and 40 degrees latitude. They derive their name from their nature as a steady, persistent wind. Trade winds affect both hemispheres: they flow from the northeast toward the equator in the northern hemisphere, and from the southeast toward the equator in the southern hemisphere.

In Hawaii we see trade winds about 75% of the year. There is a seasonal variability, with trades in place 90% of the time during the summer and about 50% of the time during the winter. During the summer, the subtropical high is very strong and persistent, and the ridge extending from the high is located far north of the state. This places Hawaii deep into the area of trade winds, and they remain quite steady. During the winter, the high is weaker and farther south, and the ridge is located much closer to the state. Because of the ridge is closer and weaker, it is easier for storm systems moving across the north Pacific to push the ridge over or to the south of the state, causing the trade winds to break down.

In Hawaii we see trade winds about 75% of the year. There is a seasonal variability, with trades in place 90% of the time during the summer and about 50% of the time during the winter. During the summer, the subtropical high is very strong and persistent, and the ridge extending from the high is located far north of the state. This places Hawaii deep into the area of trade winds, and they remain quite steady. During the winter, the high is weaker and farther south, and the ridge is located much closer to the state. Because of the ridge is closer and weaker, it is easier for storm systems moving across the north Pacific to push the ridge over or to the south of the state, causing the trade winds to break down.

Trade Wind Inversion

In the northern hemisphere, the wind flows counter-clockwise around low pressure systems, and clockwise around high pressure systems. Because of friction near the surface, the wind spirals in toward the center of low pressure systems, and away from the center of high pressure systems. As the wind spirals away from the high, air above the surface must sink to fill the void. As the air sinks, it warms and dries out. (This leads to the clear skies and dry conditions usually associated with a high pressure system.)

Normally in the atmosphere, temperature decreases with height. (The higher you go, the colder the temperature.) For dry air, the temperature drops about 5.5°F for every 1000 feet (about 10°C for every kilometer). However, the sinking and warming air near the high pressure system creates a temperature inversion—a layer where the temperature either remains the same or increases with height.

An inversion is a very stable layer. An air parcel that is buoyant will continue to rise as long as it is warmer than the air around it. (Picture a hot air balloon rising as you heat the envelope.) Once the air parcel hits the inversion, it is no longer warmer than the air around it and stops rising. An inversion is also known as a cap, since it limits how high into the atmosphere that air can rise. On average, the trade wind inversion is around 7,000 feet in Hawaii.

Rainfall

The islands themselves act as a lifting mechanism, causing air to be forced upwards. This is similar to air being forced upwards along a cold front or warm front, and is referred to as orographic lift. Across the state, the trade wind rainfall pattern breaks down into two types. Over the Big Island and east Maui, the terrain extends above the average inversion height, and the greatest rainfall occurs across the windward slopes. (The peak rainfall occurs at just over 3,000 feet in elevation). Over the remaining islands, the terrain is located below the average inversion height, and the greatest rainfall occurs over the peak of the highest terrain. There are very sharp gradients in rainfall amounts between the coast and the peak of the mountains, where the amount of rainfall increases rapidly as you move to higher elevation.

Hazards to Aviation

Turbulence: The conditions that may lead to strong trade winds (strong high pressure and a stable low-level inversion) are also those that lead to turbulence in the lee of the mountains. As a rule of thumb, winds of 20 knots may lead to light turbulence, winds of 25 knots may lead to moderate turbulence, and winds greater than 30 knots may lead to severe turbulence.

Clouds/showers: Because trade wind showers are greatest over the terrain, lower ceilings and mountain obscurations are also more likely. In addition, trade wind showers are still convective in nature, and can create localized updrafts, downdrafts, and gusty winds that can be hazardous, especially to small aircraft.

Information about our current weather pattern (including any changes to the trade winds that are expected) is covered in the Area Forecast Discussion (AFD). Aviation hazards are covered by AIRMET or SIGMET bulletins, and the reasoning behind any hazardous products will also be discussed in the AFD. All of these products are available through the WFO Honolulu website.

John Bravender

Aviation Program Manager

National Weather Service Honolulu

Pingback: Trade Wind Inversions | Flying In Hawaii